It was a great day for an escape. Maybe not such a great day to die, but for some there was no escaping that.

Imagine we were in Aiken, South Carolina: a pretty town, near Augusta and the Georgia border, with a fine mild climate (headed for the low fifties today, February first, while much of the rest of the US freezes and shovels out).

Imagine we were in Aiken, South Carolina: a pretty town, near Augusta and the Georgia border, with a fine mild climate (headed for the low fifties today, February first, while much of the rest of the US freezes and shovels out).

But we’re visiting there in 1916. Aiken’s climate is a major selling point for the town. It has numerous hotels which attract well-heeled Yankees fleeing the deep freeze of northern winters, and even the heat of summer, plus a railroad to bring them and various cargoes up and down the Southeast.

February first in 1916 was also a Tuesday, and as the Southern Railroad morning train pulled in from Georgia, the streets were already busy. A great many people of color, dressed as for Sunday churchgoing, were on the streets, heading for the old school.

There were enough of them that few noticed a family of five calmly making their way along the sidewalks toward the station: a tall couple, and three girls of school age.

But not only were they dressed in their best, they were wearing coats heavier than needed in the cool day, and carrying parcels, elderly-looking suitcases and covered baskets. If you noticed them it would be evident they meant to get on the train, not to meet someone getting off.

But they hoped no one was noticing them. They had planned for this day a long time, and with care. And part of the care was keeping quiet about it.

Let’s call them the Edgecombes. And looking close, we can see they were already tired, as if they had stayed up most of the night, or had walked a very long way to get here.

The hunch would be partly right: the parents, Simon and Ada, didn’t sleep much that last January night. And despite their fixed, deferential smiles, especially aimed at any passing whites, they were tense, like criminals plotting an escape.

Which is exactly what they were doing, escaping — though they were by no means criminals.

Simon had done landscaping work; Ada cooked, cleaned and nannied for middle class white families. It was hard work, though not as hard as the toil of their parents and grandparents, who did more of the same as slaves.

Simon’s boss man was not so bad for a white person; but he took Simon for granted, the pay was pitiful, and he clearly expected Simon to work for him til he couldn’t work any more; and then what?

Simon and Ada were not afraid of work; but they wanted a life with a future, especially for their daughters, Evangeline, Sarah and Amber. They didn’t see much of that in Aiken but more of the same for the rising generation of color. And likely the ones after that.

Besides, beyond Aiken’s resplendent scenery dotted by well-appointed stables, and brushed golf courses that kept the “winter colony” white folks diverted, the Edgecombes’ memories were seared with scenes of horror, seen and heard: especially the lynchings.

In Aiken and the surrounding counties, there had been dozens of lynchings, and they kept happening, with no recourse for victims or consequences for perpetrators. The winter people seldom heard about them, and when they did, indignant local clergymen and officials insisted the stories were lies spread by Yankee agitators.

But the Edgecombes knew better, or worse. And by 1916, enough was enough.

Simon had a great uncle Ezra, who had served with the Federal Colored Troops in the last years of the Civil War (excuse me, one still had to be careful to call it “The War Between The States” around Aiken). Uncle Ezra had survived the war, minus his left leg, then won a poker game in an army hospital, and used the money to make his way to Philadelphia.

Ezra had written to Simon in 1914, when the war in Europe had started, about jobs looking for workers in Philadelphia factories. He bragged that he was doing well, despite the wooden leg. He offered to take in the family if they wanted to come north, put them up til they could find work and get their own place. Ezra said he could actually vote in Pennsylvania, there were hardly any lynchings, and the cops were not so mean.

His letters set Simon to thinking: his father had voted a couple of times in Aiken, but got badly beat up the last time; and voting was all over with for Blacks in Carolina by when Simon turned 21. He wasn’t so sure if he believed Ezra’s claim about the Philly cops; but maybe . . . . And hardly any lynchings.

He talked to Ada: if we did it right, he whispered one night, after the girls were asleep, maybe we could make it. He spoke tentatively, wondering if Ada would think he was crazy, or be too afraid to leave their home; and whether shepherding the girls would be too much for her on such a long and hazardous trip.

He was wrong. Ada loved her Carolina people, but after years of changing white babies’ diapers, she was more than ready. So they made a plan. Then they started scrimping and saving from their meager wages.

It took two years to get enough together for the tickets. And they did plan it like burglars scheming to rob a bank at night: when Simon wrote back to uncle Ezra, he took the letters to Augusta on a landscaping job, and mailed them from there. Ada hid the coins they saved in an old sack under a loose board in the kitchen. They used a code, referring to “the church conference,” when the girls were awake; and told no one else.

Finally they had the money. Simon also went to Augusta to buy the tickets, to Philadelphia; they went into an envelope and then under the loose board. And when they heard at church about the festivities set for February first, they agreed the visiting crowd would be the best cover they could get. His boss man agreed to give him the day off, and docked his pay.

They did follow a circuitous route to the station, avoiding streets where they knew people, and it took them past the old school, where preparations were already underway. The big occasion there was to mark its fiftieth anniversary, and the birthday of the out-of-town founder.

Simon felt a twinge of guilt as they passed the school buildings. The place was completely dedicated to the program of the great Booker T. Washington. He preached constantly for black people to stay where they were, and to work, save, and get schooling there, and stay away from agitation for “social equality.” As a New York newspaper had recently echoed, “if the colored people continue securing education, property and character and cultivating in every manly way the friendship of their neighbors, their future is secure.”

Simon mostly believed that. But not all the time. Security wasn’t happening to enough Black people in Aiken, or South Carolina, or Georgia, to see much hope, or security for his children. And he didn’t understand the part about why he couldn’t vote, or shouldn’t want to. Plus those lynchings were a continuing nightmare. If the Philadelphia cops were only just half as bad . . . .

Still, he had gone to the old school for several years, as had his father, and now his daughters, and part of him felt like a traitor to them and their version of Mr. Washington’s program.

But he shook off the feeling and kept walking.

They turned in at the station, as the arriving passengers were still spilling out of the colored cars at the back and milling around; yes, good cover.

They were ready to step up into the empty car, when they heard a commotion behind them: someone was yelling.

Simon flinched and turned to see, shadowing his face with a hand and holding his breath: He felt Ada’s hand reaching for his. He shot her a furtive glance, and read the anxious question in her eyes: “Could it be your boss man has somehow spotted us?

“She’s dead!” a man was shouting, running toward the crowd at the station. A woman shrieked at the cry.

“She’s dead”, the man repeated breathlessly. “Lord Have Mercy, Miz Schofield’s dead.”

More screams and cries. But Simon let out a sigh of relief: it was not his boss man.

He turned and strode resolutely up the steps. Leaning from the doorway, he took parcels and a suitcase from Ada, then lifted Amber from her arms; she followed with Sarah and Evangeline.

This, he realized, was their underground railroad, but one that moved above ground, right under God’s sun. Many like him still had ties to their starting place which would be hard to break. But at least there were no more slave hunters with dogs cruising the city streets in Philadelphia. No “Slave-Wanted” posters with a sketch and his first name would go up. No whippings, or worse, if they were caught. What they were doing might be risky at the start, but it was not a crime.

They were among the first in the car, and fitted on two rough benches. Evangeline was whispering to Ada about Miz Schofield, but her mother nodded and shushed her.

The engineer blew the whistle and the car lurched. Simon stowed the suitcase, hung onto a strap and looked around the dingy car, then out the window.

Trees and street lamps were jerking past, and around a bend he caught a glimpse of the old school and its bell tower. If Miz Schofield really was dead, that was another mark of separation from Aiken, and as the town receded behind them, he felt increasingly safe from the boss man’s clutches.

Yet, as he swayed with the car he realized he still owed Miz Schofield a lot: she and her teachers had taught him arithmetic, enough so he could count the money they saved to escape. And they had urged him to thrift, so he could resist the temptation to waste it. They drilled him the letters he needed to puzzle out the railroad schedules.

Now he had taken all these skills, and turned them against the program that Booker T. Washington and Miz Schofield had drilled into him: “Put down your bucket where you are.”

NO! He was a free American, at least to this extent: he could now pick up his bucket, and put it and those of his family, down somewhere else. Yes, there would be a new set of problems in Philadelphia. But also new possibilities.

He sighed again. Aiken was out of sight now. His boss man was gone with it. But the bench was uncomfortable. The train rattled and shook.

It was, he thought, going to be a long ride to Philadelphia.

* * * *

The Edgecombes are fictional, but their story was like those of millions of real people: they were among the pioneers of the Great Migration, people of color determined to escape southern violence, Jim Crow oppression and poverty, and build something better for themselves and their children.

Contrary to what some local politicians charged, this migration was not instigated by “Yankee agitators.” It began spontaneously, and didn’t have a leader like Mr. Washington. But it did have much real leadership, by ordinary Black men and women who took hold of their own destiny, like the Edgecombes. And it soon developed a momentum that was massive and historic.

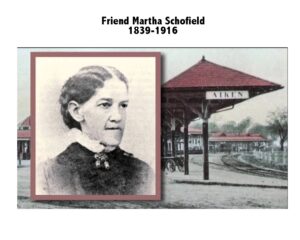

Martha Schofield was also very real. She was born on February first, 1839, in Darby Peennsylvania, north of Philadelphia. And she indeed died on February first, 1916, her 77th birthday. Hundreds of alumni of her school were indeed gathering then to celebrate her and the 50th anniversary of her school’s founding, shortly after the end of the Civil War. (One of her last acts was to order ice cream for 300.)

Schofield was a Hicksite Quaker, with Progressive Friends influences. Her family were active abolitionists, and she worked in a field hospital during the Civil War. And she was among the first cadre of volunteers from the North who felt a strong leading to go south to build schools for the newly freed people.

Although not yet thirty when she came to Aiken, she brought with her a remarkable combination of native ability and boundless energy that put an enduring stamp on the region and the state.

Starting with almost nothing, surrounded by ruthless violence, she managed to start a school which soon outgrew its small building. She taught classes, designed the new buildings, hired and managed staff, and fended off waves of organized terrorism that were destroying Reconstruction.

And not least, year after year, she raised the funds to keep the school going. Even had it been a time of peace and tranquillity, it’s hard for me, a century-plus later, to comprehend how she survived the annual round of riding on those rough early trains, in the summer dust and heat, up and back from Philadelphia and other cities, then begging and buttonholing the great and the small for dollars and dimes. And the steady stream of letters to benefactors, most done by hand. It never stopped.

And she did this on her own, for most of fifty years. Of course there were supporters, but I mean organized and managed.

She also kept a journal, and wrote many personal letters to family members and friends. While part of what’s now the very liberal branch of Friends, she was a regular Bible student, who prayed often and joined in many church services with students and colleagues. And she had a clear, distinctly Quaker sense of divine leading and vocation — and no little stubbornness–about it.

Her mother realized this early on, after trying, and failing, to persuade Martha to finish up her first year in the South and then come back home. As her mother admitted in this touching letter to Martha:

[Her mother], returning in May from a week at the Quaker Yearly Meeting, found a letter awaiting her. She was up before 5 the next morning to compose a reply:

“Thee says thee will come home for a visit if I will consent to thy going back now. Thee knows it will be a great trial to me and to us all to part with thee again but what can I say. I have always endeavored to teach my children to obey the light of Christ within them let it lead them where it might and I cannot think that now, thee says thee knows thee is in the right place, that I must say, fulfill the duty to thy heavenly father first.”

The pride with which she invariably responded to Martha’s commitment reasserted himself once more.

“Thy faith has been remarkable and I rejoice that I have a daughter that lives so near the divine foundation that she comprehends the will of her father and her ability to perform it. This is truly a great work…. Thee will see by this that I do consent to thy going.”

She admitted that Martha’s decision was not totally unexpected.

“There seems to be something so fascinating about it that all who go want to go back again.”

Actually, not all who would go would stay. Most did not: if they weren’t worn down by the rigors of the teaching, or the punishing summers, then the recurrent waves of terrorism, massacre and intimidation of the counter-revolution that ended Reconstruction sent them home with what would now be heavy PTSD.

It seems clear to me that Schofield’s turn to Booker T. Washington’s program was less a sellout than a hard-headed reckoning that, given the abandonment of southern Blacks by the federal government and the judiciary, the reconquest of the Confederate states by brutal white supremacists, that a defensive posture, aimed mainly at incremental, marginal achievements was maybe the most that could be managed for the coming decades, until some new breakthroughs came along (which didn’t really happen until forty years after her death).

One of those breakthroughs, though a slow-ripening one, was the great migration that our fictional Edgecombes typify, and truly it was largely made possible by the impact of the foundational work of Schofield and her sisters and brothers who labored so long in the dim decades of Jim Crow. But historians will argue about that forever.

Martha took breaks back in the North, but she spent the rest of her life centered in Aiken developing the school, and only flagged after the wear and tear of her seven-plus decades, and was not happy about being nudged into a kind of retirement.

Furthermore, she built for the long haul. After several days of mourning her, the former students shipped her body back to Darby for burial, and the school went on.

As it has til today: now part of the public system, as Schofield Middle School, it projects great pride in its 150 year history, and the truly remarkable Quaker activist who launched it.

Quakers should retrieve Schofield from the amnesiac oblivion she has fallen into among us; I believe she offers an example of commitment that few can match, but all could learn from, and adapt to our own difficult times.

The main biography of her is Martha Schofield and the Re-Education of the South, 1839-1916, Katherine Smedley, Edwin Mellen Press, 1987. (Not online, no Kindle edition.)

She needs more scholarly, popular and Friendly attention.

Thanks for this well-written and insightful retrospection. It yielded some insight for me into the likely experiences of my great grandparents, Barclay and Anna Johnson during their tenure (~1900 – 1903) at Southland Institute in the Arkansas Delta region, another Quaker educational outreach.

Thanks!

Her example of being led and following her leading is humbling, an example for us all.

Yes, a truly amazing woman. Thank you for spreading the word about her importance to the education of formerly enslaved people. Her ” Normal and Industrial School” taught many saleable skills and had a working farm. Her mother Mary Hough Jackson Schofield(later Child after her husband Oliver died) was the one who was from Darby, Martha was born on Swamp Rd, Newtown, Pa in a house that is still there on the Bucks Co. Community College land, near the Schofield covered bridge. The Jacksons in Darby and the Schofields in Newtown provided stops on the Underground Railroad. Martha’s dad Oliver was written out of Newtown Meeting for ” too strident abolitionism”.

Thanks for the additional info, Lydia! One could usefully go on at much length about Martha, but space & time were limited here. I hope Quaker scholars (and others) will pay more attention.

And thank you, Chuck, for your repeated reminders of our Friends’ heritage.

Hi

I am the historian at the Darby Meeting, in Pennsylvania.

I will be giving a talk on Martha Schofield March 28th, 18:00- at the Christiana Borough Hall, in Christiana PA for those interested.

Will there be a zoom link question?

Good question. I don’t know (I’m not involved in the presentation, just passing on the announcement.) Better write to ESR about that.