Norman Morrison: November 2, 1965

50 years ago, November 2, 1965, Norman Morrison, a Quaker from Baltimore, drove to the Pentagon, and walked across its broad lawns to a spot very near the office of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. McNamara was busy making decisions to expand the burgeoning U.S. war in Vietnam, a war that Morrison despised.

![]()

In one arm Morrison carried his daughter, Emily, age 11 months; in the other, a wine jug.

He opened the jug, poured the contents over himself, and lit a match.

The jug was full of kerosene. The flames shot into the air. Norman Morrison quickly burned to death. Emily was unharmed.

Why did he do it? The next day a letter arrived addressed to his wife.

Dearest Anne:

For weeks even months I have been praying only that I be shown what I must do. This morning with no warning I was Shown as clearly as I was shown that Friday night in August, 1955, that you would be my wife. … And like Abraham, I dare not go without my child. Know that I love thee but must act. …

Morrison had mailed it on his way to the Pentagon.

Morrison’s action was worldwide news.

Most Americans were shocked and horrified. Some said he must have been crazy. In Vietnam, the reaction was very different: Morrison was seen as a self-sacrificing hero.

I heard about Morrison in Alabama, where I was doing civil rights work. I hadn’t yet encountered Quakers “in real life.” I was stunned also.

Half a century later, both the action and the memory are still disturbing. I wish I could think of November 2 as I do June 1, the day in 1660 when Mary Dyer was taken to the gallows on Boston Common. She too had walked freely into her fatal encounter, defying a banishment order to be enforced with a rope.

That date is easier to deal with because, for one thing, it’s 300 more years distant, cushioned by the centuries. And for another, knowledgeable Friends generally see Mary Dyer’s sacrifice, and those of the three other Friends hanged in the same city in those years, as having been vindicated by history. Their deaths are considered key steps toward establishing freedom of religion in North America.

Mary Dyer’s witness is even carved in stone, with a statue of her seated on a plain Quaker bench, keeping quiet watch next to the Massachusetts statehouse on Boston’s Beacon Hill.

The flames that seared Norman Morrison are different for me. They are part of my life experience: while I didn’t actually see them, it still feels as if I did.

And more important, as this fifth decade since clicks over, I’m still waiting for the consolation — or is it reassurance? — that Morrison’s death accomplished something toward his goal of slowing American militarism, diminishing its bloody momentum and lethal growth.

But such signs are very few this haunted autumn, not to mention this decade. This century.

Just this past week, the same pentagon announced a $70 (or was it $80) billion dollar contract to build a new gold-plated “stealth” bomber, likely aimed above all at China. And now there will be U. S. “Boots on the ground” in Syria openly (instead of covertly); the drones are incinerating many unseen human targets daily, and the “forever war” continues. And this is not to mention the steadily consolidating police state apparatus closing in around all of us day by day. Or the flock of presidential candidates vying to out-hawk each other.

This catalog could be much longer; but the point should be clear. I don’t understand Morrison’s motivation much better now than in 1965, except for a sense of its extremity. And even though there’s probably more to the the Vietnamese government-sponsored hagiography of Norman than shrewd ideological propaganda, I’m too jaded and cynical to see it.

Is this a dim gleam of it?

Anne Morrison Welsh . . . wrote immediately to Mr. McNamara after [his 1995] publication of “In Retrospect,” [in which he expressed regret and sorrow about the Vietnam War] a book that caused hate mail to pour into Mr. McNamara’s Washington office. Enclosed was a copy of a statement she released to the press in response to his book:

“To heal the wounds of that war, we must forgive ourselves and each other,” she wrote. “I am grateful to Robert McNamara for his courageous and honest reappraisal of the Vietnam War and his involvement in it.” . . .

Mr. McNamara carries with him a copy of the public statement from Norman Morrison’s widow. He often reads aloud to the press, in an emotion-choked voice, the paragraph expressing her gratitude to him for coming forward to set the record straight.

Robert McNamara admits he weeps in public occasionally when he mentions Norman Morrison and the letter from Anne. “I get very emotional,” he says. “I get very teary. I consider it a weakness. And those particular words — the words of forgiveness Anne wrote — do make me emotional.”

In his book, Mr. McNamara writes some words of his own that are likely to elicit emotional responses from at least 58,000 American families; words that if followed by deeds would have changed their lives. And that of Norman Morrison’s family as well.

“I believe we could and should have withdrawn from South Vietnam either in late 1963 amid the turmoil following Diem’s assassination or in late 1964 or early 1965 in the face of increasing political and military weakness in South Vietnam,” Mr. McNamara writes now of his beliefs.

— From The Baltimore Sun, July 30, 1995

I recall when that book came out. And I thought then what I think now: Too late, too late.

Even so, I still speak of Norman Morrison and his action today with respect. I just wish I could do it by citing more of a resemblance between its outcome and that of Mary Dyer’s last walk through Boston.

If any of you can see that, let me know. I asked Mary Dyer, but she only kept her vigil.

From a poem by the Vietnamese poet, Tu Loo:

Emily, come with me

Sau khôn lớn con thuộc đường, khỏi lạc…

Later you’ll grow up you’ll know the streets, no longer feel lost

– Đi đâu cha?

– Where are we going, dad?

– Ra bờ sông Pô-tô-mác

– To the banks of the Potomac

– Xem gì cha?

– To see what, dad?

Không con ơi, chỉ có Lầu ngũ giác.

Nothing my child, there’s just the Pentagon.

Ôi con tôi, đôi mắt tròn xoe

Oh my child, your round eyes

Ôi con tôi, mái tóc vàng hoe

Oh my child, your locks so golden

Đừng có hỏi cha nhiều con nhé!

Don’t ask your father so many questions, dear!

Cha bế con đi, tối con về với mẹ…

I’ll carry you out, this evening you’ll going home with your mother…

Oa-sinh-tơn

Washington

Buổi hoàng hôn

Twilight

Ôi những linh hồn

Oh, those souls

Còn, mất

That remain or are lost

Hãy cháy lên, cháy lên Sự thật!

Blaze, blaze the Truth!

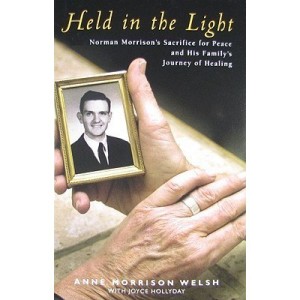

Norman’s widow, Anne Morrison Welsh, published a book about this experience in 2008: Held In The Light.

My first thought was, “That poor child.”

Chuck, I remember that very clearly. I was raised a hawk and supported the Viet Nam War. I didn’t want to go to Viet Nam on someone elses terms, so when the draft notice came, I joined the Corps.

His self-immolation was startling and gave the first of many pauses that made me reflect on my beliefs. As powerful as it was, we continue to be a warrior tribe with a tendency to animal behavior.