In 1978, a Jewish writer-activist named Arthur Waskow published a book called Godwrestling. I read the book a year or two later, and have never forgotten it.

In 1978, a Jewish writer-activist named Arthur Waskow published a book called Godwrestling. I read the book a year or two later, and have never forgotten it.

Waskow died this week, just after his 92nd birthday.

In the book he described a Jewish way of Bible reading and interpretation that was drastically different from the Christian approaches familiar to me.

His earlier career was as a leftist, secular Jewish writer and scholar. But in the fury and fires of the late 1960s, he was pulled in another direction. Waskow wrote vividly of his own journey along this path in a March 1, 1973 article in WIN Magazine:

“In the spring of 1968,” he recalled, “I began an encounter with Judaism, Yiddishkeit; in the winter of 1972, that encounter deepened into one with God.

The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob–especially the God of Jacob, who became Israel, the God-wrestler.” (Waskow, 1973.)

This encounter took the form of learning Hebrew and studying the Jewish Scriptures.

How did Waskow know when he had made this transition? He knew because he began doing something he had never done before in his career as an academic and intellectual activist:

“I knew how sharp a turning it was when I realized that for the first time in my life, I was writing poetry.”

This was not greeting card verse, either. Consider these lines from one of his earliest poems (Waskow, WIN, Ibid.):

“Wrestling feels a lot like making love.”

Why did Jacob wrestle with God, why did the others talk?

God surely enjoyed that all-night fling with Jacob:

Told him he’d won,

Renamed him and us the Godwrestler,

Even left him with a limp to be sure he’d remember it all.

But ever since, we’ve talked.Did something peculiar happen that night?

Did somebody say the next day we shouldn’t wrestle? Who?

We should wrestle again with our Comrade sometime soon.

Wrestling feels a lot like making love.”

Soon after, Waskow was part of a Jewish renewal group, a kind of alternative synagogue, called Fabrangen, in Washington. In Godwrestling, he explained that it tackled the Bible in just this way, following weekly Torah readings in Sabbath services. As he put it:

“…Every Shabbos morning, the Fabrangen wrestles God. Ourselves, and each other, and God. We do not simply accept the tradition, but we do not reject it either. We wrestle it: fighting it and making love to it at the same time. We try to touch it with our lives.

“When we touch the Torah with our lives, both our lives and the Torah come alive. We change our lives….What we are doing is what the people Israel is all about: ‘Israel,’ the Godwrestler.” (Waskow, p.11.)

Waskow is referring here to the story in Genesis 32, where Jacob wrestles with God all night, and is “rewarded” afterward by being given a new name, Israel, which means “he who wrestles with God.”

The fact that the Hebrews came to be known as the Children of Israel, the Children of the Godwrestler, and even today are called the Nation of Israel, the Nation of Godwrestlers, makes this name and concept, in Waskow’s view, central to Jewish religious identity:

“And touching the Torah gives it new life because the Torah was the result of such touchings in the first place. When Jacob wrestled, it was ‘with men and God’ at once, not first one and then the other, but the two at once–distinguishable but not separable.

From that wrestling flew fiery drops of sweat that fell into place as the letters of the Torah. For the Torah is struggle distilled into teaching…..

Generations of Jews after Jacob have wrestled with other people and with God, and the sweat of their wrestlings too became the fiery shapes on the parchment and the paper. And it is from the very pores of our own wrestle with other human beings, in the full knowledge that every such wrestle is with God as well, that we must distill our ‘theology,’ our own ways of understanding God and Torah.” (Ibid.)

When I read this, in the late 1970s, I was (and am still) situated among the Christian descendants of this same biblical text and its authors. I thought I had had a reasonable exposure to major interpretive schemas and controversies.

But this frame was utterly new to me.

Utterly new —and yet it landed with a shock of recognition. Bible study as struggle—neither mindlessly accepted nor derisively rejected — fit and illuminated my own observation and experience. It was true internally, with the Bible, and with religion generally, from my insular Catholic boyhood, into my adult years among Quakers.

Religion was not all struggle all the time; but godwrestling had been a recurrent and sometimes dominant feature, even if often repressed or ignored. Yet if anyone had described the struggles as part of these traditions’ essence — in biblical terms, as part of its “revelation” — I missed it.

I also knew just enough to see that the reality of such “godwrestling” was not confined to Judaism, or even the Judeo-Christian galaxy.

The godwrestling motif has stayed with me for nearly fifty years, and its significance and usefulness have not dimmed or diminished. Hardly.

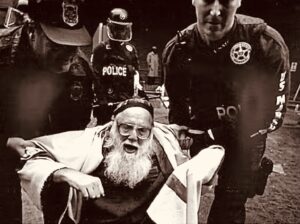

I met Waskow a couple of times, but didn’t know him. He wrote other books, with which I’m not familiar. The struggles he faced within Judaism were clearly absorbing, and have only deepened in his final years. He remained an activist until near the end.

For that matter, there has been plenty of absorbing struggle among American Quakers in those decades. Thus, Godwrestling remained an abiding and formative influence for me, enough to call for this small tribute on the passing of him who opened it to me. I finish repeating a Jewish saying, “May his memory be for a blessing.”

My favourite biblical story – Jacob and thr ‘other’ ( the man, the angel, God, the self?). It is dark. Jacob is afraid of his brother. He is by the River Jabbok, which means place of emptying. He struggles. He is hurt in mind, soul, and body. His name, his identity is changed. And out of the fearful encounter a blessing ensues. Such a rich story both psychologically and spiritually.