What “secret” am I talking about here? Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) with a secret?

A good question to ponder on her 232nd birthday: First Month (January) 3.

For her devotees, Lucretia Mott’s life is, or should be, an open book: born into a loving, encouraging family, married for 57 years to what one biographer called “the best husband ever.”

She had a long public career as a recorded minister, preaching and speaking, of which generous samplings have been preserved; for decades she was also a tireless organizer for many reform causes (including –very timely today, racial justice and an end to war) ; she left hundreds of letters, which scholars have been combing through fruitfully.

She also endured deep sorrows: the loss of two of her six children, the Hicksite-Orthodox division which split families as well as meetings; five terrible years of civil war, and then widowhood. She also outlasted and overcame decades of withering criticism of her progressive ideas and “heresies.”

None of that is new, or unexamined. But what is less clear, essentially a “secret,” is not a recipe for waffles, but the answer to a nagging question: how did she get away with it?

One clue: in her personal carriage she was a model of traditional Quaker propriety: she disdained novels as frivolous and vain; it was husband James who sat in a quiet corner, burning the midnight oil, unable to put down Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Then, while Hicksites all around were shedding the grey and the bonnet, she dressed plain til the very end.

Sure, she was wrong about some things: she forecast in the 1870s that war would soon be outmoded & obsolete. She believed, at least for awhile, in phrenology, a pseudoscience that taught one could discern intelligence and character by mapping bumps on the head.

But if there is any hidden scandal or shame, in 145 years after her death in 1880, nothing has turned up or leaked out.

But if there is any hidden scandal or shame, in 145 years after her death in 1880, nothing has turned up or leaked out.

Anyway that’s not the sort of secret I’ve been looking for. Yet she remains a conundrum: there were many other respectable matrons among American Quakers of her day who were also advocates of charity and reform; there were devoted Friendly mothers; and women ministers who traveled and spoke. That still potentially radical Quaker tradition, with its incomplete but emerging equalitarian impulse, was almost six generations strong when she was born. And still, she’s one of a kind.

Further, to say she was “controversial” is correct but a serious understatement. For years they were gunning for her — “they” being most of the Hicksite Quaker Establishment, as not only a threat to conventional theology, but to the social/economic order they sat atop of. (“They” also appeared as assorted torch-carrying anti-abolitionist mobs, with much more than “eldering” on their minds.)

Yes, the image many have of Mott and her Quaker generation is that of a phalanx of activist reformers. The image is true enough of her, and a small (but growing) band of others.

But the “official” view was quite different. Official Quakerdom was then very Quietist and hierarchical: keep out of politics, they commanded, and avoid organized public reform work, such as abolition and for women’s rights.

Why? Because organized reform work would put them alongside outsiders, and Friends were to be a “select” separate people, who did not “mingle” with “the world”. Public reform work also provoked opposition, even violence. (The elders were not all wrong about that, especially as regards slavery.)

Yes, the elders were officially “against” slavery; didn’t buy, hold or sell them. But slavery itself would end, they argued, only when God decreed it, and that must happen by God’s hand, not the soiled paws of humans.

Many Friends were disowned for becoming involved in reform work. So many that I’ve identified what I call “The Great Purge” among Hicksites: not a formal schism like Hicksite vs Orthodox, but the banishment of many — entire meetings as well as individuals— who dared to yield to the temptation of reform activism. More on this in my book Remaking Friends.

Isaac Hopper, below, was an important example: a friend of Lucretia and a victim of the Great Purge: disowned in 1842 for being an abolitionist; guilty as charged. Also steadfast: he still came to worship in his meeting and sat on the same bench til his death ten years later.

In this widespread purge effort, Lucretia Mott remains notable not least as The One Who Got Away. In my researches I’ve turned up evidence of at least half a dozen attempts to have her disowned. And these were not unknown at the time.

Indeed, one of her admirers, William Adams, a Friend of Philadelphia, kept a diary of his attendance at Lucretia’s Meeting, between the year 1841 and his death, in 1858. . . . here are his notes from two of many occasions when he mentioned her and her ministry:

Twelfth month (December) 3d. [1843] After a short silence Lucretia Mott arose and delivered a very edifying discourse, wherein the slave was not forgotten. She plead[ed] for the truth with a zeal that I thought was according to knowledge, and which, it seemed to me, her adversaries could not gainsay or resist. And at her close I thought I saw the recording angel of truth fly to Heaven and record her testimony in the “Lamb’s book of life.”

First month (January) 21st, 1844. On sitting down in meeting it came into my heart to pray for Lucretia Mott, that she might be supported in all her trials and her discouragements. May the choicest of Heaven’s blessings rest upon her, and may her sun go down in brightness and her reward be sure. Before I was through my aspirations, she arose with, “In your patience possess ye your souls,” and gave us an edifying discourse. Near the close I thought I saw the Saviour descend and stand by her, or hover over her, with, “Be not discouraged, for I am thy God.”

Second month (February) 1845. Next [in describing the ministers of Cherry Street Meeting] that precious handmaid of the Lord, Lucretia Mott. Great has been her exercise and devotion for the cause of the slave; may her reward be sure. Thou precious lamb, thou hast known what it is to be in perils through false brethren, and to be persecuted for righteousness’ sake, and thine is the kingdom of heaven. Let me here bear my testimonies to thy edifying discourses, and be permitted to say that I believe thou art not far from the kingdom. Let this record stand to enduring generations. Amen.

So the “secret” I’ve been looking for is the answer to the question that pops up almost continually during her most active years: Why didn’t she get disowned, like Hopper and so many others?

After much digging, I think I’ve figured it out: It’s because of Nantucket.

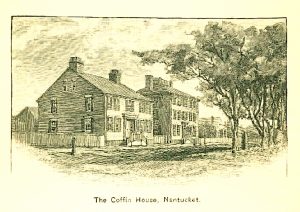

Nantucket is a small island about 30 miles off the Atlantic coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Nowadays it’s a summer resort for the very very well-heeled, with the harbor full of yachts, hobby sailors in bright red jeans, and other bobbing marks of affluence.

But Back In the Day — say the day of January (oops, excuse me: First Month) 3, 1793, [Again: Happy 232nd Birthday, Lucretia!] Nantucket was fast becoming the American capital of whaling, a substantial port for merchant shipping — and the most important Quaker stronghold in new England, second only to Philadelphia on this side of the Atlantic.

Nantucket is a fascinating pilgrimage spot for Quakers; it’s best to visit off-season, when it’s easier to see past the opulence, and grasp how thick the small town is with stirring Quaker history.

Among its numerous distinctive features, the one we want to home in on here was the fact that while the harbor was populated with Quaker ships coming and going, the town was populated by many Quaker women. And these women, even the most prosperous ones, were kept plenty busy; not just with children, but also with business.

I mean both Meeting business, and business business. Many Quaker men were away from the island for years on end (Lucretia’s father was gone for three years on one voyage), sailing halfway around the world (or farther) on trips that were always dangerous, not rarely fatal — and during which communication with home was rare or nonexistent.

Meantime, Quaker women, while still heavily encased in what we would now think of as stereotyped women’s roles, were more educated than many other females of their day; they also had official status in the Meetings; and they — well, let’s hear how Lucretia describes it—

Biographer C. M. Hare noted that Lucretia once referred to her island background and childhood, writing:

“In those early years I was actively useful to my mother, who, in the absence of my father on his long voyages, was engaged in the mercantile business, often going to Boston to purchase goods in exchange for oil and candles, the staples of the island.

“The exercise of women’s talents in this line, as well as the general care which devolved on them in the absence of their husbands, tended to develop and strengthen them mentally and physically.” [Emphasis added.]

Many Nantucket women, like Lucretia’s mother, were in business. Some from home, others had shops clustered around a street that is still unofficially called “Petticoat Row.”

Thus, while still looking very demure and conventional, many of these women were encountering and making their way in a “man’s world” of commerce, and learning much that stayed with them.

Further, Lucretia wrote to Elizabeth Cady Stanton that:

— As to Nantucket Women, there are no great things to tell. In the early settlement of that Island Mary Starbuck bore a prominent place, as a wise counsellor, & a remarkably strong mind.

— Divers Quaker women since that time, have been eminent as preachers. . . . Hannah Barnard of Hudson [New York], a native of Nantucket, of the last century, was regarded one of the greatest ministers in the Society. She travelled in England, & was there deposed by the ruling powers ^in the Society of course,^ for daring to express doubts of the Divine authority of the Jewish Wars—as well as far more openly than Friends were wont, to deny the atonement & scheme of Salvation. She returned home to Hudson & was much respected thro’ a long life for her good works.

“No great things to tell”?? Who’s she kidding!

The whole Nantucket community and culture was largely founded by a towering matriarch, Mary Coffin Starbuck (Lucretia’s great-something-or-other aunt; can’t keep all the genealogy straight). Then:

— The early Quakers still earlier 1660 & 70 asserted & carried out Womans equal claim to the Ministry—& reciprocal vows in the Marriage covenant—also in acting a part in the Executive duties of the society—while their women too were & they still are governed by laws, in the making of which they have no voice—rules of Discipline always issuing from men’s M[eetin]g— Some advance in this respect in Rhode I. Yearly—& Genesee; as well as entire equality in the Progressive Frds. Mgs . . . . (Emphasis added)

And here, I think is the nub of it:

. . . In the Mo. Mg. of Friends on that Island, the Women have long been regarded as the stronger part— This is owing in some measure to so many of the men being away at sea— During the absence of their husbands, Nantucket women have been compelled to transact business, often going to Boston to procure supplies of goods—exchanging for oil, candles, whalebone—&.c.— This has made them adept in trade— They have kept their own accounts, & indeed acted the part of men. [Emphasis added.]

— Then education & intellectual culture have been for years equal for girls & boys so that their women are prepared to be companions of man in every sense—and their social circles are never divided. Successive generations of this kind of mental exercise have changed improved the form of the head, and the intellectual portion predominates— Set down as much of this to partiality & self-praise as thou please.

— Lucretia Mott, Letter to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, March 1855, from Selected Letters, p. 234.

Now, let’s talk some turkey here: Quaker women, in Nantucket’s unique setting, were learning the ways of worldly commerce. Plus they had to carry on most of the business of the Meetings, which were central institutions of their culture, often acting “the part of men,” in an era when gender roles were still sharply separated.

But there’s more. Maybe I’m reading between the lines here, but I don’t think so: the Quaker sailors, like Lucretia’s own father, eventually came back to port. And when they did, they expected to take up their defined roles, as paterfamilias, and in the superior “men’s meetings” in their Quaker preserve. (What? Quaker men with tender male egos? Does the pope wear beanies?)

So the women learned not only the business of commerce; they not only managed the “business” of their large Monthly Meetings; they also learned how to make sure that the seafaring Quaker males, once they returned, were able to feel as if their status and roles had been preserved, not diminished or usurped, in their absence.

It had to be a delicate, stately Quaker dance. Women’s ways. Don’t tell me there weren’t such things that girls like the young Lucretia took in with their mothers’ milk.

Another way to say it is more secular: along with the basics of worldly commerce, Nantucket Quaker women learned Quaker politics: ins and outs beyond the basics of formal rules and protocols. It wasn’t taught in their schools. Yet thee may be sure there was instruction in the subject then — as there needs to be now. (Quaker politics? If this is news to thee, Friend, there’s some important things yet for thee to learn.)

Lucretia hinted at this in a letter to a friend much later:

Geo[rge]. Combe [a major advocate of Phrenology] told me the sculls of the native Anglo Saxon, in the earliest day were far inferior to our later developments— Nantucket women’s frontal organs are more prominent than those of women whose intellectual powers & business talents have not been called into action.

—Lucretia Mott, letter to Richard D. Webb, 2nd Mo 1870, Selected Letters, p. 435

Now this last may be Phrenological tomfoolery & pseudoscience, problematic for many modern minds. Yet it points us toward the secret, the answer to the question of HOW did Lucretia avoid getting disowned in year after year of upsetting the conventional Hicksite applecarts, and tweaking the stuffy, compromised Quaker Establishment?

No, Lucretia, it wasn’t the bumps on thy head.

After all this, it’s basically simple: she was a better, smarter Quaker politician than the men who came after her; and many of the women too. She was always one step ahead; there were close calls, but she repeatedly slipped from their grasp.

And besides her native intelligence, of which she had plenty, and her courage (ditto), where did this shrewdness come from? It was not cynical, or even ambitious. It enabled her ministry; and it was a Nantucket export as real as spermaceti candles.

Nantucket is part of all her biographies, of course; but I don’t recall seeing anything like an adequate analysis of how its specifically female Quaker heritage was crucial to her success in hanging on to her membership in turbulent times. She managed this even as she kept speaking up, and coping with the growing influence it enabled, in decades which led to civil war outside the Society, and something close to that within. I have some ideas about it, though not yet the time to flesh out the nuances and put them all together. (But again, for more, dig into my book, Remaking Friends.)

But that’s okay. It’s just another example of how, even at 232, Lucretia Mott just doesn’t get old.

One other point: in their pioneering struggle to articulate and advance the rights of women, Lucretia and her “sisters” found many new ways to raise hell (or make John Lewis’s “good trouble”) in their larger society. And they did it without winning any elections — because they couldn’t vote, til several decades after Lucretia’s death in 1880. Personally I think that studying their tactical agility could measurably enhance related activism today.

Note: The following story is probably apocryphal. But it’s too good to pass by here.

In the early 1830s, a young man went to sea, hoping to make his fortune. A Presbyterian by birth, he read his Bible each night in his shipboard hammock, and he was haunted by a verse in the fourth chapter of Proverbs:

“Wisdom is the principal thing: Therefore, get wisdom: and with all thy getting, get understanding.” Wealth, the youth piously decided, was nothing without this seasoning of wisdom. But where was such a combination to be found?

Presently his ship sailed into the harbor of Nantucket Island. Nantucket was then a wealthy and vibrant community, built and largely populated by members of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers.

As he walked the bustling, cobbled streets of Nantucket town, observing the fine grey shingled houses and the plain but prosperous inhabitants, another verse from Proverbs came to him. It was something about “I am Wisdom, and in my right hand is riches and honor.”

The more he saw of Nantucketers, the more he felt sure that here was a group that genuinely understood and knew how to apply this practical profit-generating kind of Wisdom.

When he turned down one street, known then as “Petticoat Row,” he saw a succession of neat, prosperous-looking shops and stores. Almost all were operated by Quaker businesswomen.

The sailor was so impressed with this commercial tableau that he impulsively entered one of the shops, a kind of grocery store. He walked up to the counter and said to the plain-dressed woman behind it, “Madam, I want to know why you Nantucket Quakers seem so wise in the ways of the world.”

The Quaker woman said to him, naturally very humbly, “Well, of course, it’s mainly because we follow the Inward Light. But,” she added, “it’s also because we eat a special kind of fish, the Wisdom Fish.”

“Wisdom Fish?” the sailor exclaimed. “What’s that? Where could I get some?”

“Friend,” the Quaker shopkeeper said, “thee is in luck. I just happen to have one here, which I can sell thee for only twenty dollars.”

Twenty dollars was a lot of money in those days, but the sailor didn’t hesitate. He pulled out his purse, handed over the money, and she gave him a carefully wrapped parcel, which he carried out of the shop with an excited smile on his face.

He returned a few minutes later, however, looking puzzled and a bit disturbed. “Excuse me, madam,” he said, laying the half-opened package on the counter. “This is nothing but a piece of ordinary dried codfish.”

Under her modest white bonnet, the Quaker shopkeeper raised one eyebrow.

“Friend,” she said quietly, “thee is getting wiser already.”

Wow again! Great stuff with societal ramifications.

How do the serfs learn to find their way? By having roles learned from childhood where they are not acting as serfs.

Where is that going to happen? That’s the question.

Quaker Meeting is one good place that comes to mind — if we who populate said Meetings were to open our cultural doors to those unlike ourselves.

Thanks. This points to many doors that need opening.

That was great, Chuck.

Great story (The Wisdom Fish)! I suspect it is true. If not, there’s an even greater chance it was written by a Quaker woman – not a man.

Thank you, Chuck.

Lucretia Mott, what an inspiration.