J. Deotis Roberts, a pioneer of Black theology, dies at 95

Washington Post — August 16, 2022

By Harrison Smith August 16, 2022

The night of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, the Rev. J. Deotis Roberts was attending a conference at Duke University, listening to German theologian Jürgen Moltmann present a paper on the theology of hope.

Dr. Roberts, a soft-spoken Baptist minister and theology professor at Howard University in Washington, had spent years wrestling with philosophical questions about God, existence and meaning. Now he began to wonder what Moltmann’s theology — what any theology — had to say to “a hopeless people” living in an age of anger and despair.

-

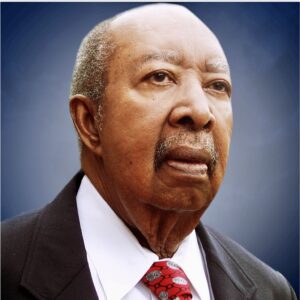

The Rev. J. Deotis Roberts in 2007 at his home in Bowie, Md. (Charmaine Roberts Parker)

The next morning, he asked Moltmann how his approach to Christianity might be applied to Black Americans. The German scholar had no answers.

“It was then,” Dr. Roberts later wrote in an essay, “that the seed of ‘black theology’ began to germinate in my own mind.”

Dr. Roberts went on to help pioneer Black theology, a new perspective on Christianity that evolved in response to the revolutionary spirit of the Black Power movement, with a focus on issues of racial justice and liberation. “I am pleading for a theology of the Black experience which grows out of the soil of our heritage and life,” he wrote in a 1976 article for the Journal of Religious Thought, outlining his vision. “For us faith and ethics must be wed. There can be no separation of the secular and the sacred. Jesus means freedom.”

A first-generation Black theologian, Dr. Roberts rose from an upbringing in the segregated South, where the county prison was within sight of his elementary school, to become the first African American to earn a doctorate from the University of Edinburgh’s divinity school in Scotland. His work emphasized both liberation and reconciliation, drawing from King’s emphasis on nonviolence as well as Malcolm X’s message of Black self-determination. As he saw it, the church had an obligation to address social issues and engage with the daily struggles of marginalized people, including African Americans.

“No theologian of [Christianity] can escape the ethical questions raised by racism,” he wrote in his 1971 book “Liberation and Reconciliation,” “whether white oppression or black response.”

Over the decades, Dr. Roberts’s work became “a touchstone” for generations of Black theologians, according to his former student David Emmanuel Goatley, director of the Office of Black Church Studies at Duke Divinity School. Dr. Roberts was 95 when he died July 22 at his home in Clinton, Md. His daughter Charmaine Roberts Parker confirmed the death but did not cite a cause.

For years, Dr. Roberts was engaged in an intellectual dialogue with the Rev. James H. Cone, who effectively launched Black theology as a formal discipline with his 1969 book “Black Theology & Black Power.” While Cone emphasized the need for liberation, Dr. Roberts insisted that reconciliation was just as important. “He did not want to support any notion of freedom, of liberation, that would in any way create separation,” said the Very Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary in New York.

“If Cone was more spurred on by a Malcolm and the Black Power movement,” she added in a phone interview, “then Roberts was more like a King,” emphasizing a message of nonviolence and reconciliation while pointing to “Christ’s universal relationship to all humanity,” not just White people, who often depicted Jesus as a blond-haired, light-skinned messiah. “For Roberts,” Douglas continued, “Black people had as much right to see Christ in their likeness as did anybody else.”

Dr. Roberts liked to say that he lived “with one foot in the academy and one foot in the church,” and preached and taught at churches while spending much of his academic career at historically Black institutions. He taught at Howard’s divinity school for 22 years before leaving in 1980 to become president of the Interdenominational Theological Center, a consortium of seminaries in Atlanta. He was later a distinguished professor of philosophical theology at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary in the Philadelphia suburbs, and in 1992 he was elected the first Black president of the American Theological Society, one of the field’s oldest professional associations.

He felt an obligation, he said, to help “overcome the cancer of racism” afflicting seminaries and other religious institutions, in part by bringing more people of color — and more women — into leadership positions. For many years he also taught alongside Latin American theologians at a seminary in Buenos Aires and collaborated with scholars from around the world, focusing in particular on Black theology’s African spiritual heritage.

“Roberts applied himself and his genius to building important bridges between African Americans and Euro Americans; the church and the community; older and younger generations; traditional and contemporary cultured expressions; and between prophetic and praise-based church traditions,” said Adetokunbo Adelekan, a theology and ethics professor at Palmer Theological Seminary, the successor to Eastern Baptist.

“In so doing,” Adelekan continued in an email, “he helped to expand our imagination about the role of the seminary and the church and where the future of the American Church may be.”

The youngest of three children, James Roberts was born in Spindale, N.C., on July 12, 1927. His father was a carpenter, and his mother was a homemaker. According to his daughter, he took the middle name Deotis at the suggestion of his elementary school principal, who said that it meant “learned man” or “scholar.”

He went on to graduate from high school at 16 and studied at historically Black universities, receiving a bachelor’s degree from Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte in 1947 and a bachelor of divinity from Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., in 1950. During his studies, he supported himself in part by serving as a pastor.

Dr. Roberts earned a master of sacred theology degree in 1952 from Hartford Seminary (now Hartford International University for Religion and Peace) and received his doctorate in philosophical theology five years later. In part, said Goatley, he completed his education in Scotland because of racial barriers at American divinity schools: “There were exceedingly few opportunities in the United States for an African American to be able to pursue a PhD in theology or philosophy.”

The year after he got his doctorate, Dr. Roberts joined the Howard University faculty. He took a leave of absence in the mid-1970s to serve as dean of the theology school at Virginia Union University in Richmond, and taught at Eastern Baptist from 1984 until 1998, commuting to the campus in Wynnewood, Pa., from his home in Silver Spring, Md. Later he taught for three years at Duke.

Dr. Roberts published more than a dozen books, including the essay collection “Quest for a Black Theology” (1971), which he edited with James J. Gardner; “A Black Political Theology” (1974); and “Bonhoeffer and King: Speaking Truth to Power” (2005), which explored the theological perspectives of King and German minister Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

His wife of 66 years, Elizabeth Caldwell Roberts, an elementary school teacher, died in 2019. In addition to his daughter Parker of Clinton, Md., survivors include two other daughters, Carlita Roberts Marsh of Washington and Kristina Roberts, a best-selling author who writes under the pseudonym Zane and lives in Atlanta; eight grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter. He was predeceased by a son, Deotis.

After he started writing about Black theology, Dr. Roberts appeared at conferences and church gatherings to discuss his views, including at a 1989 conference in New York City where speakers noted some of the problems facing Black Americans, including poverty and violence.

“In some respects, we’ve gone backwards in this decade, and racism itself has become more insidious,” he told the New York Times at the time. “If our people are to survive,” he continued, “it will be largely due to how well the Black church carries out its mission.”

Harrison Smith is a reporter on The Washington Post’s obituaries desk. Since joining the obituaries section in 2015, he has profiled big-game hunters, fallen dictators and Olympic champions. He sometimes covers the living as well, and previously co-founded the South Side Weekly, a community newspaper in Chicago.

![]()

https://garrisonkeillor.substack.com/p/butch-thompson-you-will-be-missed

BUTCH THOMPSON – YOU WILL BE MISSED!

Nov 28, 1943 – August 14, 2022

Born and raised in Marine-on-St. Croix, a small Minne-river town, Butch Thompson was playing Christmas carols on his mother’s upright piano by age three, and began formal lessons at six. He picked up the clarinet in high school and led his first jazz group, “Shirt Thompson and His Sleeves,” as a senior.

After high school, he joined the Hall Brothers New Orleans Jazz Band of Minneapolis, and at 18 made his first visit to New Orleans, where he became one of the few non-New Orleanians to perform at Preservation Hall during the 1960s and ’70s.

In 1974, he joined the staff as the house pianist of public radio’s A Prairie Home Companion. By 1980, the show was nationally syndicated, and the Butch Thompson Trio was the house band, a position the group held for the next six years.

From the early days on APHC, Butch remembers, “It was pretty casual back then. Margaret or somebody would call me and ask if I was busy on Saturday. More than once I remember saying I couldn’t get there by showtime, and being told to show up as soon as I could. Sometimes I’d go onstage without remembering what key something was in. If Garrison was going to sing, I usually couldn’t go wrong with E major.”

By the late ’90s, Thompson was known as a leading authority on early jazz. He served as a development consultant on the 1992 Broadway hit Jelly’s Last Jam, which starred Gregory Hines. He also joined the touring company of the off-Broadway hit Jelly Roll! The Music and the Man, playing several runs with that show in New York and other cities through 1997.

The Village Voice described Butch’s music as “beguiling piano Americana from an interpreter who knows that Bix was more than an impressionist and Fats was more than a buffoon.”