Revelation on Rose Street

New York City – A Fine Autumn Day in 1843

I was still feeling a bit weak that first Day morning, after several days in bed with a bilious fever. But I was now better, and the weather in New York was fair.

My good wife agreed that a walk to Meeting would likely do me good. It was only four blocks to Rose Street, after all.

Several men Friends were milling around near the broad meetinghouse steps, on their way into the plain brick building. But one lingered, not going in. His tall figure was unmistakable even though his grey coat and broadbrim hat were like all the others.

Several men Friends were milling around near the broad meetinghouse steps, on their way into the plain brick building. But one lingered, not going in. His tall figure was unmistakable even though his grey coat and broadbrim hat were like all the others.

It was Simon Goodloe, and he was standing on the top step, looking over and past the rest, evidently waiting for someone. And I thought that someone must be me, because as soon as he recognized me he came striding down the steps, long legs moving like those of a graceful grey crane, and extended his hand.

“Jacob Hicks, I heard thee was ill,” he said, his grip firm.

“I’m better,” I answered, “but grateful to be here.”

“Good, good” he said, and I could tell from the repetition that asking after my health was a lead-in to something else.

“Um, I wonder if thee’s seen any newspapers this week?” He asked. When I shook my head, he reached into his coat. “Then thee may not know of the bit of difficulty our George White faced in Philadelphia last First day.” He handed me a folded sheet of newsprint.

Unfolding it, I thought about habitual Quaker understatement: “a bit” of “difficulty”? In regular conversation, “a bit” was a small amount, or a trivial event. But those sorts of “bits” were not recorded in our newspapers. Nor did their echoes swirl like a gale up the Atlantic coast, setting signal flags, topsails and tongues flapping all the way to Manhattan’s docks. Goodloe was being ironic.

I squinted and scanned the small print quickly, and my eyes widened.

“Good lord,” I said. “An actual riot? In the Cherry Street Meeting? And wait” — I squinted again — “it says here the Philadelphia police were called? Police? To a Friends Meetinghouse? What—“

Goodloe’s long face was solemn. “It was all incited by that abolitionist agitator Stephen Foster.”

I glanced down at the sheet. “What did Foster do?” I asked.

“What they always do,“ he said, “tried to turn peaceful Christian worship into a disorderly abolitionist rally.”

“But — “ I protested. “A riot in one of the largest meetings in our republic? “How—??”

Goodloe charged on: “Foster’s impertinent intrusion was too much for some of the younger men Friends, it seems.”

He hovered as I read some more, mouth agape, then pursed his lips. “Roughed him up like a pack of stevedores,” he said, closing his right hand into a fist and thumping it into his left palm. “Didn’t exactly turn the other cheek, I suppose” he mused. Again the irony. He did not seem very upset about it.

“Simon—“ I began.

“Yes, perhaps it’s unseemly of me to take any satisfaction in this report,” he admitted. “And Jacob, I can’t deny it: I’m grateful this, er, unfortunate incident did not occur here at Rose Street. But I’m not sorry to see those infernal abolitionists shown by firm discipline that Friends want nothing to do with them, or their noxious doctrines.”

He paused, took a couple deep breaths, then once more gazed over me down the street.

Was Simon, I wondered, waiting for another Friend, or perhaps watching out for someone?

“Jacob,” I said, “surely this Foster would not try anything like that here . ..?”

I now recalled having heard Foster’s name before, and knew he had in fact disrupted numerous worship meetings. He hectored various sects, but seemed to take special pleasure in disturbing Friends meetings with his infidel notions. And there were others like him.

“I doubt we’ll see Foster here,” Simon said. “He spent the night in the Philadelphia jail, licking his wounds, then was fined $250. And even with help from his accomplices like Lucretia Mott and her radical ilk, that’s a lot of money. It will take him awhile to recover.

“No, Jacob” he continued, “I’m more concerned today about our home-grown abolitionist troublemakers.”

I nodded. “Thee mean, Charles Marriot and James Gibbons?”

“Indeed,” he said. “In thy time of illness, thee may likewise not have heard that their appeal of disownment was rejected by the Yearly Meeting Committee three days ago.”

“I had not,” I agreed. “Three days ago, I was thinking only of my aching joints, and unsettled stomach.”

“Yes,” he said. “Thee looks to have recovered well. But I don’t think we need worry about them. Gibbons is away, I am told. And Marriot was eldered by a committee which urged him to find another place to worship, and he said he would.

“So,” I said, “that leaves only–“

“Yes,” Simon said. That leaves only Isaac Hopper.”

Isaac Hopper, I thought. The third person in our own unholy trinity. An amiable enough fellow, to talk with, not as aggressive as Foster. But hard as flint when it came to abolition. The Rose Street elders had summoned me to join the committee that warned him he was risking disownment if he stayed on the board of the New York Abolition Society.

It was a disagreeable mission, but a matter of duty.

It also meant I had to listen to him declare, not belligerently but still rather pompously, that he would be honored to suffer on behalf of the voiceless slave, even in this comparatively small way. He spoke calmly, but the words smoldered: he was a lifelong Quaker, and disownment was not a small thing to him.

Yet there was no doubting his resolve. He was soon launched into the standard abolitionist catalog of charges about whips and chains and selling slave children away from their families, again calmly but implacably.

“When last we met,” I said aloud to Simon, “I was able to cut Isaac short, by reminding him sharply that Friends have been free of owning or selling slaves for more than fifty years.”

I rubbed my chin. “But Hopper simply said that all the Quakers who had done that were long since dead,” I continued, “and in the meantime the number of slaves in the country had increased by millions. He couldn’t stop. ‘The question for Friends today,’ he said, ‘is not what our ancestors did then, but what we shall do, now.’”

Goodloe touched another long finger to the newspaper. “Did thee see that the trouble broke out at Cherry Street after Foster’s message was denounced by another Quaker minister.”

“Was that George White?” I asked.

Goodloe nodded. “Of course.”

George Fox White — our most renowned and forceful minister. If he was visiting Cherry Street when Foster had accosted Philadelphia Friends, no wonder things got out of hand. White preached powerfully that slavery was evil, but just as powerfully insisted that its fate was in God’s hands, not man’s.

And so slavery would end, as it must, White said, but that end would come only in God’s own time, and happen by God’s mighty hand, not by human agitations.

Abolitionism, he thundered, is no more than some men arrogantly trying to force God’s hand. That was blasphemy, he boomed, and put them and many innocents on the road to bloodshed and ruin. It was no less than an abomination.

For years, George White had preached this judgment in Friends Meetings from Boston to Indiana, to large and mostly welcoming audiences. He warned them all that abolitionism meant only trouble, not just for Quakers, but for our entire young nation. And many ugly incidents in those years had seemed to confirm his forecasts.

All of us at Rose Street remembered the sad fate of Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, built to be a national hub of abolitionist work. Some of us had even quietly sent donations for its building fund. But two nights after it opened, the hall was burned to the ground by a proslavery mob. That was in May 1838, hardly five years ago.

Hopper knew all this. His back had stiffened and his eyes flashed when I reminded him of it. But his voice was still calm, and even a bit lower: ‘Simon,’ he said, ‘I can only tell thee my convictions: that we are all called to be the hands of God in this world, as best we can. And that all time is God’s time, which includes our time. We are to put these hands to God’s work now, today, with all we have. And Simon,’ he said, ‘liberty to the captives was in the very first message Jesus preached. That is the part of God’s work I am striving to join.’

Goodloe rolled his eyes. “Needless to say, our committee was unmoved by the melodrama and left him soon after.”

I nodded: Its verdict was swift and clear: Isaac Hopper, along with Gibbons and Marriot, were told they threatened the unity and reputation of the Society of Friends by their abolitionist actions. They were thus declared to be out of unity with Rose Street Meeting, and disowned by Friends.

But being disowned, I knew, did not prevent an offender from attending worship– unless he was expected to be disruptive, like Stephen Foster. But that did not fit Isaac Hopper. He was determined, yes; but calmly so. He had, in fact, been seen at meeting here at Rose Street every First Day since the committee acted, taking his regular seat up front. But quietly so.

In which case, why was Simon Goodloe waiting to see if he would appear today? The meeting had, I could tell, begun settling into quiet. We were late, lingering and prattling there on the steps.

A thought came to me. I tapped the news clipping. “How far has this Philadelphia story spread?” I asked.

His expression turned rueful. “Far enough,” Simon said, “to be read by Armistead Merriwether.”

“Who?” The name was strange to me. It didn’t sound Quaker. More like someone southern.

My intuition was right. “MISTER Armistead Merriwether, Esquire,” Simon said, emphasizing the titles which Friends normally avoided. “Of Savannah, Georgia. He’s an agent for many large southern planters. And a client of Goodloe and Goodloe.”

“Ah,” I said. “He saw this report too, then.”

“Yes,” Goodloe agreed. “On his way to New York, on one of Goodloe and Goodloe’s ships, loaded with cotton. He came with it to make sure everything was in order here.”

“Which it was, I’m sure,” I said. After all, Goodloe and Goodloe was one of the largest and most respected American shipping firms.

“On the ship all was well,” Simon said. “But when he saw the article at a stop in Baltimore, Merriwether resolved to make sure all was in order off the ship also.”

Simon removed his hat and wiped his brow, though the air was not all that warm. Then he clamped it back on his head, frowned at an unpleasant memory, and affected a southern drawl.

“‘Mr. Goodloe,’ he mimicked, ‘I am aware that your people have different views about some of our southern customs. Now I can live and let live, suh: you all follow your conscience, and we follow ours. But my planters need to be sure of that policy.”

He cleared his throat. “You know, as I know, there are other shipping companies in New York, firms operated by men of other faiths. ‘Presbyterians, for instance. Now the Presbyterians have made it clear to us that they too are on board with a live and let live approach to social matters. Can you, Mr. Goodloe, suh, give me similar assurances to take back to Savannah?’”

My mouth gaped. “What?” I almost shouted to Simon. “Well I never!”

The very idea that he was questioning the good faith of a Quaker firm like Goodloe and Goodloe. “It’s unheard of!”—

“Thank thee, Jacob,” Simon said, “for thy high opinion of us. But I must say that, despite my high regard for thy opinion, unless thee also has many boatloads of cotton for my ships to carry, I must also pay very close attention to the views of MISTER Merriwether.”

The sarcasm in Simon’s tone was most unusual, but the point was clear. For Goodloe and Goodloe, admiring Friends were welcome. But customers, of whatever faith, were necessary.

“As he said,” Simon added, “Merriwether is not bothered that we shun the slaves

trade. But association with the abolitionists, who want to free all slaves in the south, including those who grow and harvest the cotton – . Well, neither he nor his planters will tolerate that. “

He gestured again at the newsprint. “Does thee know, Jacob, they have now made it a crime — a felony, five or more years in their dreadful prisons— to simply distribute any papers like this questioning slavery in the southern states?”

I had indeed read of those recent disturbing laws. “So, what answer did thee give Merriwether?” I asked.

A small tight smile crept onto Simon’s face. “What does thee think?” He said ruefully. “My answer was to invite him to join us here at worship. Especially with George White back from Philadelphia and speaking for us in the meeting. I’m counting on the sobriety and good business sense of Rose Street Friends to be so evident that Merriwether will come away with all the assurance he could hope for.”

So THAT’s who he was waiting for. Not Isaac Hopper at all.

Now Simon was peering down the street again, and his face seemed to brighten, though with what seemed to me a forced air of welcome. “There he is now,” he whispered, waving one arm.

I glanced around, and saw a large man striding toward us. His white linen suit stood out like a flag, even from half a block away.

“If thee don’t mind,” I whispered back, “I will join the meeting,” and went past him through the men’s doors.

The large meeting room was nearly full, women on one side, men on the other. An usher directed me up the stairs to a seat in the gallery.

The room was quiet. From my perch, I saw Simon and Merriwether enter and brush past the usher to take Simon’s accustomed place near the middle.

And a few rows further up, there was Isaac Hopper, in his usual seat, silent and seemingly serene.

The quiet did not last long. A minister rose in the elevated facing benches at the front and began to preach.

His message was something about the spiritual importance of arriving at worship in a timely manner, as we were exhorted to do in our Book of Discipline. Then another minister soon stood, doffed his hat, and began to pray for the safety of all those who sailed the perilous seas, and for government officials bearing the heavy burdens of state, and for all others who were burdened, of which he had a lengthy list.

Nothing very radical, or interesting so far, I thought.

But then, after a short silence, a stocky figure stood, in the body of the meeting, and began to speak.

It was George White. He first admitted being guilty of a breach already spoken of, as he had arrived late, and so was not in his accustomed seat on the facing benches with other ministers. But then he began his message proper, which was another version of his abiding plea to put all our burdens and problems onto God and Jesus. We were to turn to them, he said, because as hopelessly sinful men (and women) we could do nothing for ourselves.

He spoke for almost an hour – I admit I covertly checked my pocket watch– and this for him was a relatively brief sermon. His passion carried us with him. As he continued he also made sure to denounce abolitionism as an abomination, along with Temperance societies and the new groups who wanted to gain more legal rights for women.

These too were among his usual targets: all, he insisted — all were faithless, useless inventions, he said, prideful efforts by men (and women) to displace and hinder the work that belonged to God alone. All were blasphemous and bound to fail, and to create havoc and misery as they did so.

As he finished, I looked around the room. As usual, it was evident that his message was being well-received by most of the Friends.

Once White sat down, I expected the elders on the facing benches to shake hands to mark the close of worship.

But before they could do so another figure was standing. I leaned forward for a better view: yes, it was Isaac Hopper, who almost never spoke.

At once I felt a twinge of anxiety: was Hopper now, with nothing to lose, going to join Stephen Foster in …bringing abolitionism into Rose Street and challenging George White? Was he about to dash the hopes of Simon Goodloe to retain Armistead Merriwether’s confidence and trade?

I needn’t have worried. After surveying the group for a moment, on whose faces were many expressions of caution or even hostility, he spoke:

“I am reminded this morning,” he intoned, “of those words of Jesus, among the last that he spoke on the cross. They are recorded in the twenty-third chapter of the Gospel of Luke. He said, ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they are doing.’”

Forgive whom, I wondered? The elders, along with me, who approved his disownment? The southern slaveholders whose property he meant to snatch away from them? George White, for condemning reformers like Hopper himself? Or something else, perhaps of a personal nature?

But that was all; Hopper then sat down. I breathed a cautious sigh of relief, and my questions began to dissipate. The elders quickly shook hands, and we stood.

A few minutes later, I saw Simon introducing Merriwether to George White. I couldn’t hear what the southerner said, but he was all smiles. And above him, Simon’s face wore an unmistakable look of triumph. Whatever Isaac Hopper’s cryptic quote had meant, it made no difference here. So it seemed as if Simon Goodloe had obtained for his visitor the assurance he sought, or something close to it.

But as I left the building, there was a tap on my shoulder.

I turned to see Isaac Hopper at my side. In his hand was a piece of paper, which I recognized as the same newspaper clipping. “Thee saw this, Friend?” He asked quietly.

“Yes,” I said.”From Philadelphia.”

He glanced down at the text. “Jacob,” he said, “I do believe those who incited the attack on Stephen Foster can be forgiven. As can those who have wronged me and others here.”

He folded the paper and slid it back into his coat. “But I believe something else, too: God’s forgiveness aside, those who think they have put an end to something, in Philadelphia and here in Rose Street, are very much mistaken.”

He shook his head. “My case here may be finished. But others will follow, and the matter of liberty to the captives is not over. No, not at all.”

Before I could think of a reply, he touched his hat, said, “Good day to thee, Friend,” and walked down the steps and up the street.

Watching him go, something struck deep within my inward parts, like a stone sinking into my belly. I could somehow feel that, whatever Simon Goodloe and Mr. Merriwether had arranged this morning, it was Isaac Hopper, the offender now disgraced and cast out from among us, who was right about the future.

And as this sense settled over me, I began to feel unsell again, so turned toward home, headed back to bed.

– – – – –

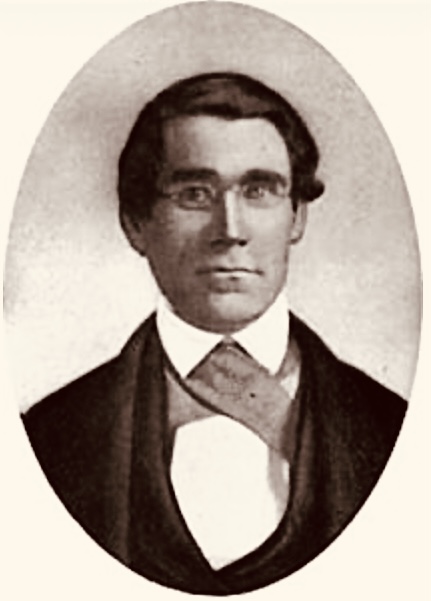

Historical Notes: While this story is fiction, it includes much history: Isaac Hopper and George Fox White, Marriot & Gibbons were real Quakers, and followed the paths sketched above.

Rose St. and Rose Street Meeting were also real in lower Manhattan (and both are long gone). Similarly, Quaker shipowners played very active and important roles in the rise of New York as a worldwide seaport, and included at one time some of the city’s wealthiest citizens. And not least, the Quaker Establishment’s opposition to abolitionism in these late antebellum years is well-documented. As also is the deep involvement in the vast trade of slave-produced goods, plus their widespread efforts to cut off its fringe of radical Quaker supporters (such as Hopper: all is incontestable. Most Quaker histories now prefer to focus on the beleaguered fringe; but while they may deserve their shafts of posthumous renown, they spent most of their lifetimes in the shadows, as part of a widely-despised, marginalized and oft-suppressed minority in most of their church family.

All doubt cast aside either that “the north opposed slavery” or that “Quakers were abolishionists “.

A bit more complicated than that. I had first heard of Stephen Symonds Foster this past spring from a talk by Arnie Alpert, recently retired director of NHAFSC and my neighbor in Canterbury NH, where Stephen Foster was born and grew up. His wife, Abby Kelly was perhaps more of an activist than he. Both were abolishiomists and supporters of equality for women.

Another good one, Chuck. Thanks for keeping at it.

Hi Anne!

I wonder if there have been any joint biographies or historical novels about Stephen and Abby. I read some about them for my book, “Remaking Friends.” And the phrase “GREAT STORY” kept popping out of the pages at me, blinking like an Electric billboard. From their meeting, to the up and down courtship, their child, their ongoing activism, ups and downs of midlife and after — it all just reeked of a dynamite story, waiting for a DYNAMITE storyteller. I’m not the one, unless somebody has an AI time-reversing machine that can make me thirty years younger. But its there, just waiting. Think about the movie or TV series.

Hi Anne and Chuck.

I have not run into any novels about Stephen Foster and Abby Kelley. There is a biography of Abby, Ahead of Her Time, by Dorothy Sterling. Worcester Bicentennial Commission published a booklet about them, by Nancy Burkett, in 1976.

Most of Stephen’s disruptive escapades took place in NH, MA, and ME. I have not seen reference to anything in PA but would love to know if there are stories. The most detailed account I’ve seen about Stephen at a Quaker Meeting was a July 5, 1842 article by Garrison in The Liberator about an incident at Lynn.

Hi Arnie Alpert,

Thanks for your note. Stephen Foster’s misadventure in Philly opens my book “Remaking Friends” as below. Alas, the text of the book on my phone (from which I’m writing) does not include the footnotes; but I can send them when I get home. It’s all documented.

Peace,

Chuck Fager

From “Remaking Friends,” Chapter 1:

Book details at:

https://tinyurl.com/y7dw4n93

I

Whatever way I read it, the whole thing feels like a setup:

December 10, 1843. Cherry Street Meeting, Philadelphia. First Day morning; the place was packed.

Much of the crowd had come expecting to hear a visiting minister, George Fox White from Rose Street Meeting in New York City. But as the meeting stretched on, the visitor sat silent.

White was one of the best-known Hicksite Quaker preachers of his day. He drew large crowds, and managed to hold them through long discourses.

Finally he rose. After quoting the Gospel of Matthew, he began:

“While sitting in great intellectual barrenness and deep poverty of spirit, with you, my brothers and sisters, this morning, through the condescension of our ever-merciful Heavenly Father, I have been allowed to turn again and again to the fleece,** and am often led to believe that I might sit in silence among you; but still, after turning the fleece, I feel my weakness increase, until, from necessity, I have been compelled to stand up before you. . . .

**[“Turn again to the fleece” is an expression taken from the biblical Book of Judges (6:38-39), in which God instructs Gideon by making a fleece wet or dry “on demand.”]

White continued for an hour and a half. XXX And near the end of his remarks, he drove home a particular concern:

“Your God has pointed out landmarks which should always be in your eyes—principles for your action which should never bring you to trample upon justice—never bring you to wrest from your fellow beings their properties, or their rights—never find you in houses of worship to which you can lay no claim . . . .

“If a man should go down to the wharves in front of your city . . . To have a hogshead of sugar and three tierces of rice sent to the Humane Society . . . and he should be called upon by their owners to know why you have taken my property; and he should reply, it was from a sense of duty— it was on behalf of suffering humanity—it was revealed to me as my duty, would you believe it? Is there one in this assembly who would sanction that robbery, or that theft, as the case may be?

“That is no greater infringement of justice, than it is to go into a house of worship— to enter a religious society, different from our own, and then, without previous consent, to break in upon their worship? I care not who shall do it: it is a delusion of the devil. Justice never required it.

“I know well that this religious society has been slandered . . . by modern slanderers it has been declared that the sons of the morning did this thing and did that. Never was a greater calumny uttered. They never did this thing, or the other, as alleged, and I challenge the world to prove it if they can.”

What was this? No evidence of early Friends (“the sons of the morning”) disturbing other churches? What about the testimony of George Fox himself, in Chapter Three of his Journal, where he recounts causing two such “disturbances” himself? (And lots more.)

But we must not get stuck on this point, though White repeated it. There was a method to the assertion:

“. . . . oh! May the arm of the mighty God of Jacob be as eminently put forth to strengthen the arms of the standard bearer of this day, in holding up the testimony of the truth, as it was to strengthen the arms of the sons of the morning in their day. . . . So far as I am acquainted with the history of the Society, there has not been a single instance recorded of one of our friends disturbing other societies.”

At length he finished. But almost as soon as he sat down, a younger man stood up and began to speak.

He was Stephen S. Foster (no, not the one who wrote “My Old Kentucky Home”). Then the meaning of White’s tirade became clear.

Foster was an abolitionist organizer. And George Fox White despised abolition and other reform groups and their “hirelings,” and preached against them regularly. Two months earlier, in another address at Cherry Street, White had thundered, “Depend not, then, I say, upon the Temperance Society, or the Abolition Society . . . which rely upon the strength of man, and not upon God. I say this in the face of heaven, these are abominations in the sight of God, and in the presence of the angels.”

And now, standing before him and the assembled multitude was a minion of just such an abomination, “breaking in” upon the worship.

Foster’s presence was no surprise. He was well-known for speaking at churches against slavery. He had been at Cherry Street the previous First Day, and had stood up then, to ask permission to speak, which was denied by someone in the raised gallery. Now he was back, not giving up.

But he didn’t get out more than a few words before the crowd was on him. From an eyewitness report:

“Great excitement in the meeting ensued. Several persons approached Foster to take him out. By this time, all was confusion and disorder. Some were crying, ‘Order! order! order!’ Others, ‘Carry him out! out with him,’ &c. &c. Women cried, several screamed, and every thing was in complete confusion.

“It was surprising to observe the malignity manifested toward Foster. To see the eagerness evinced to get at him, one would really have supposed that he had committed some most criminal outrage. . . . The most prominent of those who were for seizing him were young men, members of the Society. The first individual who took hold of him was a plain Friend.

“In the midst of the melee, our friend Geo. Bradburn, who seemed alarmed for Foster’s safety, turning to the elders and overseers on the gallery, asked- ‘Do you think it is the intention of these Quakers to cut Mr. Foster’s throat?’ It was replied, that the persons he alluded to ‘were not Friends.’ He ‘thought they were,’ he said, ‘as some of them were dressed in the garb of Friends.’

“I ought to have mentioned that Foster, in an interim of comparative order, made a second attempt to speak, and was saying something in allusion to the practice of ‘Jesus Christ,’ when George White interrupted him, saying, ‘Jesus Christ never sanctioned thy proceedings, and never will.’

“. . . In the tussle, Foster had lost his cloak and hat, and they took him, thus, bareheaded, down [the] street, with a large crowd around him, to the Mayor’s office. There he was put into a dark cellar– the usual lock-up, I believe– and kept till the Mayor could be brought, which was in about half an hour afterwards.”

Foster was released on $250 bail, and faced a hearing before the Mayor the next day. The alderman who had taken Foster to jail said he had only done so to protect him from violence. Another former member of the meeting spoke on Foster’s behalf that the attack was entirely contrary to the Quaker’s normal practice. No charges were filed.

“So ended the matter, so far as legal proceedings are concerned,” a newspaper report said. “But the excitement and discussion which it has given rise to, is not likely soon to terminate; and where the final end will be, doth not yet appear.”

Foster was not unfamiliar with such assaults. He had been badly beaten outside a Unitarian church in Maine the year before, when a pro-slavery mob vowed to prevent him from speaking there. But to be thus assaulted in and by attenders at a Friends meeting was unexpected.

Or was it? In White’s text, taken down by a stenographer, especially the call that “the arm of the mighty God of Jacob be as eminently put forth to strengthen the arms of the standard bearer of this day,” it is not hard to detect a biblically-“coded message”, or to translate it: The “God of Jacob” was a warrior, especially when “his arm” was put into action. His “standard bearers” (a standard was a battle flag) were likewise warriors; and a call to those of “this day” to put their “arms” to work against any outsider who should commit the sin and crime of invading their sanctuary–especially in league with an “abomination before God”–well, frankly, it seems a pretty plain case of incitement. And it worked.

It’s not the only one either. In September, 1845 another notorious abolitionist organizer, Abby Kelley, rose to speak in a session of Ohio Yearly Meeting (Orthodox) in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. She had an Orthodox Quaker background, but it made no difference: she was jumped and dragged out too — though in that case, a sympathetic neighbor nearby gave her a refuge and a platform on her front porch, and Kelley managed to give a fervent anti-slavery speech to a crowd that gathered around her there.

But there was an upside to this mayhem: Foster and Kelley were clearly on the same wave-length. By that December, still lecturing Ohio, they paused long enough to get married.

And they raised hell happily ever after.

But so did George Fox White.

Why the hostility? Let’s see if we can find out.. . .