Dog Days Profile: Jim Corbett, Sanctuary Prophet of Post-Desert Quakerism

Friend Jim Corbett, of Pima Meeting in Tucson, died on his Arizona ranch August 2, 2001 after a short illness. He was 67.

With his passing a quiet Quaker giant departed.

I for one am grateful to have lived in the same two centuries as he. For those who become familiar with the important strands of Quaker thought and action of our time, I believe Jim’s life and work will loom even larger with time.

Not that we’ll see a lot of monuments to him; he deserves them, but that wasn’t his way, and Quakers aren’t much for it.

But a tribute is due, and here’s mine. It’s an adaptation of a profile of Jim that was part of my book, Without Apology.

Part I

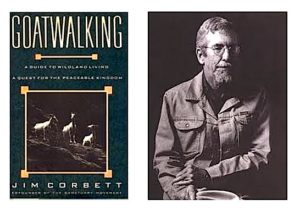

In a treatise entitled Goatwalking, you might not expect liberal Quaker “prophecy” to be a prominent theme. But in the case of Jim Corbett’s stunning book, you would be mostly mistaken.

I say mostly because it’s hard to characterize Goatwalking–or its author. If I call him a prophet, it is not because he pens jeremiads. Corbett was a gentle man, retiring, soft-spoken, grizzled by desert sun and wind. He worked as a rancher, cowboy, horse trader, librarian, shepherd and wilderness guide.

He also breezed brilliantly through college in three years, and finished a masters in philosophy at Harvard while spending most of his time partying. He cited the classics of Western–and Eastern–thought with the same familiarity and confidence that he explained how a human can become part of the society of goats.

In the course of his “errantry” (one of his favorite terms, which means a quest for personal and spiritual adventure, best exemplified by Don Quixote), there were ups and downs: Corbett once considered suicide, he says, after a series of personal setbacks in the early 1960s. But instead, after an unexpected personal mystical experience, he chose to live, and then “turned Quaker” as the best expression of his renewed view of life. He eventually settled south of Tucson, Arizona with his wife Pat, and attended Pima Meeting.

Corbett was by no means a conventional social activist. But one night in the early 1980s, he volunteered to help find legal assistance for a Salvadoran refugee arrested by the Border Patrol. But before he could file the required forms, the Salvadoran was abruptly deported, in defiance of the U.S. government’s own current laws.

Corbett was shocked, then galvanized. From this spontaneous effort to respond to the refugees’ plight sprang what became the 1980s Sanctuary movement.

The movement was not unlike the later Occupy upsurge, only more low-profile, and based in religious communities. Decentralized and officially leaderless (Corbett was the inspiration and catalyst, but he never held any formal position in the movement, and worked to keep it a decentralized network of religious communities).

Sanctuary eventually involved hundreds of churches and synagogues across the U.S. It helped thousands of refugees who fled massacres and wars in Central America — wars that were mostly supported by U.S. government policy. As part of this policy, the refugees were mischaracterized as “economic migrants,” and many were deported, with more war and death waiting for them.

The saga of the 1980s Sanctuary movement is something of an underground epic, a counter-narrative to the triumphalist “Morning in America” posturing of the Reagan-George H.W. Bush years. And predictably for the times, as the movement developed, it first put Corbett’s weatherbeaten visage on national TV, and then got his name on the FBI’s wiretap list.

Federal prosecutors worked long and hard to put him behind bars, in one of the more significant political trials of the 1980s. The effort misfired, it turned out, because a wiretap recorder had run out of tape just at a point where Corbett was on the phone making self-incriminating plans to rescue more refugee families.

Besides Goatwalking, Corbett’s unique career of “errantry” had the makings of a fascinating, offbeat suspense thriller (which I’d like to write someday). But it was a particular discovery made in the course of his Sanctuary work that I want to mention here: along with making friends and jousting with the feds, he said he unexpectedly found the Church, and with it what he called “the prophetic faith.”

Before these encounters, however, Corbett spent years in the practice of Goatwalking‘s title: wandering arid rangelands with a herd of goats. On these excursions, he and the herd became a part of the natural landscape, moving outside the standard, schedule-obsessed, nature-dominating way of life most of us lead most of the time.

The practice of goatwalking is not for the faint of heart, however: once he was asked to bring along some teenaged students from a Quaker experimental educational venture, the John Woolman School in California for a week’s trek, but they only lasted a few days. There was, they complained, “nothing to do.”

This was precisely the point, of course; but they couldn’t bear it. How many of us could?

Yet Corbett notes that the reflective, often mystical experiences evoked by goatwalking, though formally “useless,” are hardly unproductive, especially in one important field:

“Leisure, solitude, dependence on uncontrolled natural rhythms, alert concentration on present events, long nights devoted to quiet watching–little wonder that so many religions originated among herders and so many religious metaphors are pastoral….As a way to cultivate a dimension of life that is lost to industrial man [and woman], goatwalking may put us in touch with a mystery more real than we are.”

(The religions which originated in wilderness experiences include not only Judaism, Islam and Christianity, but also a little-known sect which germinated in the wanderings of a youth who in 1643 “left my relations, and broke off all familiarity or fellowship with young or old…[and for more than three years] fasted much, walked abroad in solitary places many days….” If England lacks deserts, it still had its share of wilderness, both outward and inward, in which George Fox wandered alone for several years.)

Part II

It was Corbett’s intimate familiarity with the Arizona-Mexico border country that made him invaluable in the early days of what was to become the Sanctuary movement. Indeed, it made him the movement’s founder, as much as anyone. And it was the religious encounters he had then, while working to help Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees crossing the Arizona border to escape from the bloody wars raging there in those years which brought about another major personal turnaround for him.

Fleeing imprisonment, torture and death in their homelands, the refugees all too often faced imprisonment, torture and death in the Mexican underworld, or prisons there and in the U.S.–not to mention the prospect of deportation back into the hands of bloodthirsty military governments from which they had fled.

As the refugees kept coming, Corbett kept working with them. Soon he traveled anonymously through Mexico and into Guatemala, tracking hunted exiles. More than once he narrowly escaped capture by hostile authorities. In these journeys he came to know not only the victims, but also people from many different churches who were dedicated to aiding them.

Once he joined a priest in a visit to refugees in a filthy Mexican prison. The priest introduced Corbett as “Padre Jaime,” and explained that the gringo’s non-clerical language and gestures were characteristic of his peculiar order, La Sociedad de los Amigos. Later the priest even introduced him to an archbishop as un quákero muy católico–a description which Quaker theologian Robert Barclay would likely have approved.

It was among such people of faith within outwardly quite different sects that Corbett began to sense the presence of something beyond the visible denominational structures–what he called “the church.” And not just any church, but the “Catholic” church:

“During recent weeks,” he wrote in a letter to friends in mid-1981, “I’ve been discovering this catholic church that is a people rather than creed or rite, a living church of many cultures that must be met to be known.

“I’ve been discovering the Catholic Church, not by studying Catholicism but by meeting Catholics. Whatever our creedal differences, we meet as one people by virtue of our allegiance to one kingdom. And my discovery is that the church is truly catholic, a people of peoples that incorporates not only a multiplicity of nations and cultures but also divergent beliefs, rites and perspectives….”

Still, one outcome of this discovery, he noted, was that

“After having been Quaker for almost two decades, I decided to seek formal membership in my meeting, in order to join the church….Until I began discovering the church, I had no intention of becoming a member, because I thought of denominational membership as separative rather than unitive…. [But] Just as there’s no generic form of marriage that transcends and precludes marriage to someone in particular, there’s no generic form of membership in the church I’d come to know.”

His experience of the Church both resembled and differed from that laid out in Robert Barclay’s classic 1670s Quaker theological treatise, The Apology. It is similar in its indifference to institutional boundaries, and the shift from capital to small “C”. For Barclay, the church

“is nothing other than the society, gathering, or company of those whom God has called out of the world and the worldly spirit, to walk in his light and life ….There may be members of this catholic church not only among all the several sorts of Christians, but also among pagans, Turks [Muslims], and Jews.”

Corbett differed from Barclay on one major point, in that for him the church is not primarily a collection of individuals, but rather “a people of peoples.” It is an organic network of persons working from within traditional structures that are meaningful to them, with people in other faith groups, for common purposes, or in a common pilgrimage in response to a common call. Perhaps a useful metaphor for this might be a patch of wildflowers, variegated in color, size and form, yet all leaning parallel under the breath of the same invisible wind.

Corbett doubted that this notion of church can be adequately expressed intellectually: “This is the kind of meaning one discovers only in meeting those who share it, much the way a language lives among a people rather than in a dictionary’s afterthoughts.”

Many another eminent Friend would have understood what he was driving at, I think. And as to what or who it is that animates and moves them, what lies behind the word “God,” Corbett paraphrased Job (38:2), “This is where words darken counsel and all names are blasphemy.”

Yet if words are hazardous, we are not without images. The model for this process also comes from the Bible, in the molding of the heterogenous Hebrew tribes into the people Israel at Sinai by their response to the divine calling mediated by Moses. This models the committed community, cutting across lines of culture, denomination and philosophy, which constitutes “the church,” Corbett concluded.

Furthermore, his explorations in the Bible, particularly in the prophets and the Book of Job, began to make plain to him that the experience and community of the Church, as reflected there, was one which could “bridge differences of creed, rite and culture. It even transcends the division between believers and unbelievers.”

Unbelievers, he added, like himself.

Part III

What? Jim Corbett, this quakero muy catolico, an “unbeliever”?

Yes. Shortly after his 1985 indictment on federal charges of conspiracy and “alien-smuggling,” Corbett was feted at an interdenominational religious program featuring Holocaust historian Elie Weisel. When Corbett’s turn came to speak, he startled the admiring crowd by describing himself as an “unbeliever.”

“That is,” he explained, “I don’t believe selfhood survives death, and I consider any conceivable God to be an idol.”

And yet, his “unbelief” was not conventional agnosticism or atheism, he explained. “As I read the Bible, this kind of unbelief is entirely consistent with the faith of Abraham and Moses and achieves classic expression in Job.” (Corbett had later spoken about this at the 1989 Friends Bible Conference in Philadelphia.)

Corbett pointed out that the biblical faith, as embodied in the first three commandments brought down from Sinai by Moses, put opposition to idolatry at the top of the list; and in the Book of Job, the smooth conventional theologizing of Job’s friends is relentlessly debunked, showing that idols include not only statues or golden calves, but concepts of God–dogmas and theologies–as well.

Corbett illustrated this conviction of biblical anti-theologizing by citing the prophet Isaiah, through whom God declares,

“I am the Lord, and there is no other…. I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace and create evil: I the Lord do all these things.” (Isaiah 45:5-7)

This is in stark contrast to many other passages, and to orthodox theology, where God is spoken of as all-Good.

Such biblical demythologizing of the Bible itself, Corbett said, reaches its zenith in the Book of Job, where the notion that God must be only the source of good is completely undermined. In a modern parallel, Corbett noted a report that some rabbis in Auschwitz put God on trial for injustice and pronounced a guilty verdict.

What are we left with then? Not with atheism, Corbett said, but without much formal theism either; this is, instead, the basis of biblical “unbelief,” namely that

“…the biblical faith has always required honest God-wrestling….Consider: Abraham, ‘the father of believers,’ was the ancient world’s trail-breaking unbeliever and iconoclast, rejecting all of humanity’s purported Gods….The prophetic faith has never ceased to need its idol-breakers who question all authority. Over many centuries, it has also developed a profoundly seasoned piety that can be amused by the Yiddish punchline: If You forgive us, we’ll forgive You.'” (Goatwalking, p. 6)

This was a process Corbett understood; it was much of the basis of his own self-identification as an “unbeliever.” And it had a lot to do with his attraction to the Society of Friends. He was drawn by our attempts at radical simplification of the business of religion, the stripping away of outward paraphernalia on which new forms of idolatry can hang as on hooks; and our emphasis on letting lives preach through faithful response to leadings, rather than being bound by dogma or ritual. He cited with Quakerly approval Psalm 62:1: “My soul waits in silence for God only,” and the rabbinical comment that Silence is “the worship least likely to make an idol…silence is the height of all praises of God.”

To sum up: Corbett encountered in the Sanctuary movement a new manifestation of authentic religion, which takes form in communities that respond to the leadings of an unimaginable but real presence which theologians typically call God. These communities, especially as they work together, moving in concert even while maintaining their specific identities, make up the true, “catholic” church, cutting across lines of dogma, denomination and culture.

The mission of this invisible “church” is, in Corbett’s terms, the “hallowing of the earth.” To hallow means to make holy; and the holiness we are called on to manifest is capsulized by the prophet Micah (6:8): “He has showed thee, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of thee, but to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with thy God?”

In the gospels this task is described in Matthew 25:31-46, where we heard Jesus telling of the separation of the sheep from the goats at the last judgment: the division is made not on the basis of belief or denomination, but according to whether a person has, like the heretical Good Samaritan, been “moved with compassion” (Luke 10:33) and fed, clothed, housed and defended “the least of these, my brethren.” (Matt. 25:40)

For Friend Jim Corbett, and many faith communities in the borderlands of the American Southwest and elsewhere, these texts came vividly alive as they joined in the work of providing sanctuary for some of the thousands of refugees fleeing the horror of war in Central America.

After his trial, sanctuary work continued, but as media attention faded, Corbett returned contentedly to his home, his goats and other livestock, and his writing. According to one news report, when his last illness came over him, he hurried to finish work on a new book, which was, according to one friend, “a mixture of cabbalistic and Jewish thought and his cow work.”

I smiled at that. How thoroughly Jim to mix Jewish mysticism with cows. But if anybody could do it, he could. And he’ll make it good to, I bet. I’m anxious to read it.

Note: Jim’s second book was published in 2005 as, Sanctuary for All Life: the Cowbalah of Jim Corbett. More information here.

More “Dog Days” posts . . . .

More “Dog Days” posts . . . .

One thought on “Dog Days Profile: Jim Corbett, Sanctuary Prophet of Post-Desert Quakerism”